The history of the BMW logo is as controversial and enigmatic as the history of the company itself, and it begins in the dying months of World War One…

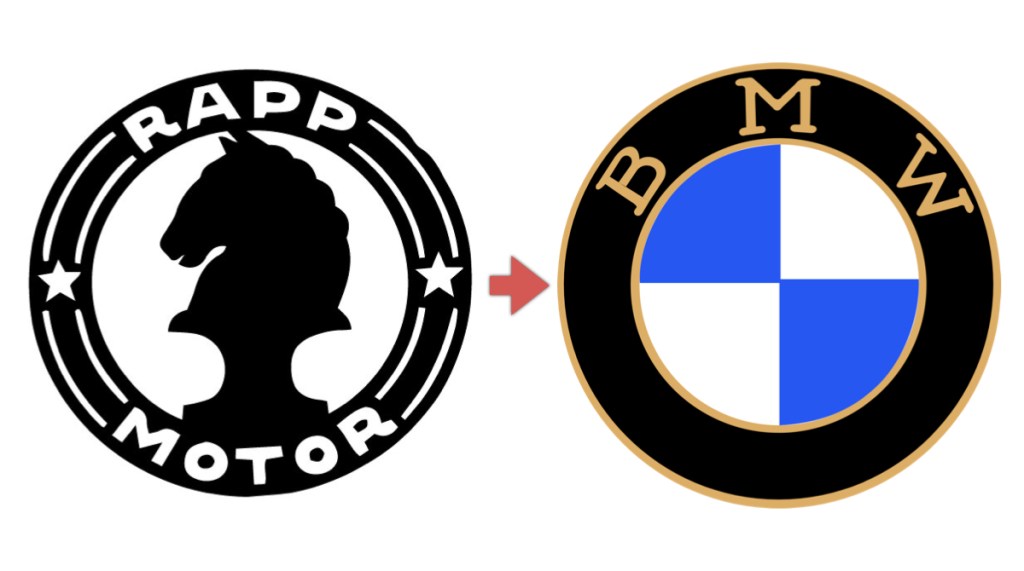

BMW can trace its roots to the Rapp Motorenwerke, created in 1913 by Karl Rapp. Developing and building aircraft engines on the outset of WW1, the business saw moderate success until Rapp’s departure in 1917. It was then renamed the Bayerische Motoren Werke (Bavarian Motor Works), yet this new firm had no logo for months, only its registered name. The reason is simple – it didn’t need one; its sole customer was the German Air Force.

It was on 5th October 1917 that the famous blue and white badge was trademarked. The colours are those of the Bavarian national flag, and it carries the tradition of a black border from Rapp’s own logo bearing the company name. By then, BMW was already deep into development of an aircraft engine the likes of which hadn’t been seen before. Named the BMW IIIa, it was an inline six-cylinder capable of 200hp at a height of over 6000ft. When bolted onto the Fokker D VII, the German Air Force had an aircraft that could out-climb and out-maneuver anything the allied nations could send against it.

The small company faced unprecedented demand for ever more IIIa engines, and over 700 were eventually built. But this success came too late to change the outcome of the war, and Germany finally accepted defeat on 11th November 1918.

When the victorious allies placed the BMW IIIa on a test rig, the results astounded them. Clocking 230hp, it represented a leap in technology far greater than anything they had come up with. In fact, so scared, so terrified were they, that the Treaty of Versailles was given an extra clause – BMW were no longer allowed to design or build aircraft engines.

Facing imminent collapse, the company shifted to the manufacture of farm equipment and industrial engines. This interwar period was a difficult time for BMW, and there came a flurry of take-overs, acquisitions and mergers in the German market that it somehow managed to survive. Coming out the other side producing automobiles with a new confidence, the firm made a nod to its aircraft origins (and a ‘screw you’ to the Versailles Treaty) with an advertising campaign portraying its badge as a stylised whirring propeller.

And so the legend of the BMW logo being a stylised white propeller against a blue sky was born. In the decades since, it has become an urban myth, and one that BMW itself has not distanced itself from, stating, “it is not strictly true there is a propeller in BMW’s logo.”

Instead, it seems BMW’s marketing team views it more as a happy coincidence they are content to allow to endure through the years. And it makes a great story, one that its millions of loyal customers can tell at dinner parties whilst admiring their BMW key fobs.

Certainly it is a far more palatable story than the one that comes from the ashes of World War Two. If you were to have shown the BMW logo to any one of the survivors from German concentration camps such as Dachau and Auschwitz, their reaction would surely have been one of horror and revulsion. Towards the end of WW2 in 1945, more than half the 56,000 workforce at BMW were used as forced labour from concentration camps. These people were made to work more than 12 hours a day, were whipped, beaten and even killed for the most trivial of mistakes. Reduced to drinking toilet water to survive, BMW’s mass production for the German war effort could not have succeeded without them.

For the longest time, BMW made every attempt to conceal its participation in the atrocities, and only began accepting their responsibility in 1999 once the vast majority of direct victims had passed away and were therefore unable to claim any kind of compensation.

Against this backdrop, BMW made the latest iteration of their logo in 2020. On its unveiling, the words of its Senior Vice President Customer & Brand Department, Jens Thiemer, must surely leave him a sour taste in the mouth:

“BMW becomes a relationship brand. The new communication logo radiates openness and clarity,”

Jens Thiemer

Or perhaps the change is rather fitting. By uglifying the brand, perhaps BMW is sending a message – that the openness and clarity they claim to hold themselves to is revealing a dark, murky past still coming to the light.

It also fits well with my own assertion in a previous post – we can’t make beautiful things anymore.