Of those passengers and crew who were lucky enough to escape the disaster alive, none have a story so downright intriguing as the ship’s chief baker, Charles John Joughin

From the moment the Titanic struck the iceberg in the final minutes of 14th April 1912, Joughin’s otherwise normal life changed forever. Employed as the ship’s chief baker catering for many hundreds of passengers, he became an unlikely hero through his many and varied actions across a huge swathe of the ship. His incredible story reads like a Hollywood script, and his actions on that fateful night of the sinking can only make a person wonder at what they would do if they were spending the final hours on a doomed, majestic cruise liner with access to sumptuous first class facilities, and an inexhaustible supply of first class liquor.

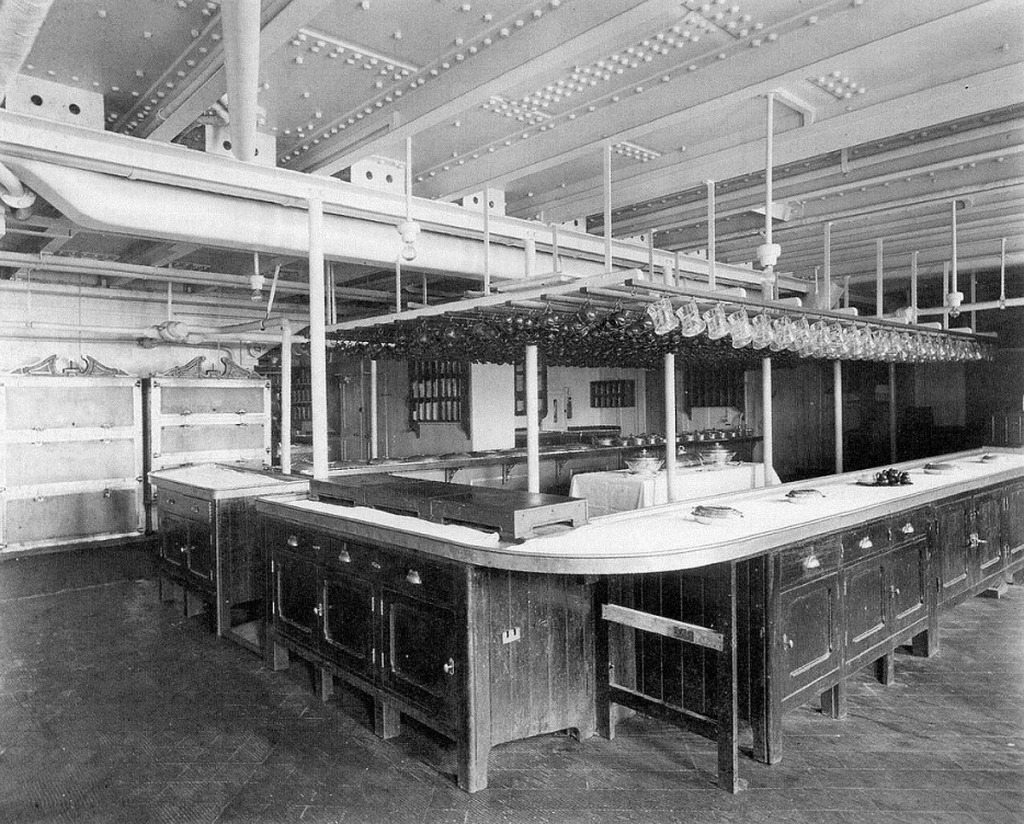

As Chief Baker, Joughin had responsibility for thirteen bakers, all catering for the ship’s hungry passengers. At the time of the collision, he was tucked up in bed in his own quarters on E Deck. Roused from sleep by a combination of the impact and hurried feet shuffling out in the corridor, he emerged from his room to hear a general order go out for the lifeboats to be provisioned.

Knowing he had a bakery full of fresh loaves ready for morning breakfast, Joughin ordered his bakers to grab four loaves each and make their way up to the boat deck to supply the lifeboats before they would be swung out and lowered. As all thirteen bakers headed up with sacks of sweet-smelling bread, Joughin hung around the shop on his own and enjoyed a quiet drink to himself. It wouldn’t be his last of the night.

In fact, Joughin spent some time partaking in the shop’s supplies as he didn’t manage to reach the boat deck himself until half past midnight, a full fifty minutes after the collision. Having selected the most expensive spirits that caught his eye, he even retired to his room for a while to continue his impromptu drinking session. Meanwhile, passengers and crew were charging up and down the corridor outside, putting on life-preservers and gathering their most valuable belongings.

In the event of an emergency, every crew member was assigned to a specific station from where they would help in evacuating passengers. Joughin’s station was at lifeboat 10, on the port side where Second Officer Lightoller was busily organising the ship’s evacuation.

By this point, the boat deck was crammed with anxious passengers, many of them torn over whether to climb into a flimsy-looking lifeboat, or stay on the doomed but safer looking ocean liner. Having made sure his allocated boat had been provisioned with fresh bread and water, Joughin began helping Chief Officer Wilde to load it with women and children. By the time they’d gotten it half full, they were finding it difficult to find women willing to leave the Titanic, so the tipsy Joughin came up with an idea.

Persuading three other men to join him, he climbed down to the deck below and forcefully dragged any woman he could lay his hands on up to the boat deck. Presumably with them fighting every step of the way, he picked them up one at a time and threw them into lifeboat 10 until it was filled to his satisfaction.

His exact words at the British Inquiry when asked if he placed these terrified women into the boats:

“We threw them in. The boat was standing off about a yard and a half from the ship’s side, with a slight list. We could not put them in; we could either hand them in or just drop them in.”

Charles John Joughin

At this point, most people would have considered this an adequate discharge of their duty, and they would have climbed aboard their allocated lifeboat to cap off what would have certainly been the night of their lives. But not Joughin. His night was only just beginning. Having filled his lifeboat with women both angry and terrified in equal measure, he stoically stood back to allow other crew members to jump aboard and be lowered away to safety.

At the Inquiry into the disaster, he was asked why he didn’t attempt to escape in the very boat he’d been allocated to;

Well, I was standing waiting for orders by the officer to jump in, and he then ordered two sailors in and a steward – a steward named Burke. I was waiting for orders to get into the boat, but they evidently thought it was full enough and I did not go in it

Charles John Joughin

It’s a simple explanation and one that deserves a stoic salute – most men would have railed at the unfairness of the situation, but Joughin was clearly not most men. With the lifeboat sent away, and nothing obvious to do with himself, Joughlin went ‘scouting around’ as he called it, and returned to his room where he enjoyed a few more drinks from his alcohol stash. By now, there was a definite list of the ship at the head, and lower compartments were flooded. Even his own room was submerged by ankle-deep water while he put his feet up and enjoyed a tipple. It must have been obvious the vessel was doomed and its loss would be imminent.

Now nicely drunk, Joughin made his way back up to A Deck only to find all the lifeboats had gone. The remaining passengers were in a state of panic as they ran from one side of the deck to the other in blind hope there would be one last boat that might get them off the doomed ship.

Displaying incredible alacrity, Joughin began collapsing the Titanic’s deck chairs and threw them overboard to give himself something to cling to when the inevitable final plunge of the ship occurred. And he didn’t just throw out the odd one or two – he threw about fifty overboard. Talk about rearranging deck chairs…

He was now so drunk, he didn’t notice the ship was listing at all. But his actions in throwing out the chairs at least gave some hope for those desperate people in the freezing ocean who otherwise would have had nothing to cling onto. Meanwhile, all this effort had made Joughin thirsty again, and this time he went down to the pantry deck towards the rear of the ship for another drink. While quenching his thirst, he heard an almighty crash as the Titanic began to buckle under her own weight. He heard a rush of people above his head and went back up to see what was going on.

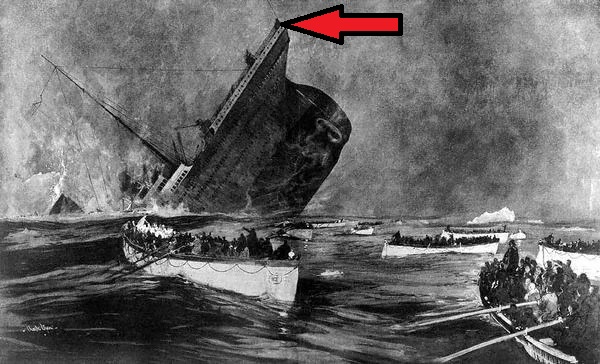

The Titanic was in its final throes of life. As the bow sank beneath the water, her stern rose, lifting her propellers clear into the air. This massive strain was too much for her keel, and the ship essentially broke in half. As the rear half crashed back down into the sea, a huge crowd of passengers who had climbed up to the stern to stay out of the freezing water were now tossed down into the well deck, a huge number of them dead or seriously injured from the violent impact.

Only one man remained clinging to the stern rail. And that man was Charles John Joughin. He was alone in the pitch dark, the Titanic’s electrics finally severed, dousing its remaining lights. But even now, he didn’t let the situation overwhelm him. As the stern rose up again to an almost vertical climb, Joughin stood on the outside of the metal hull at the rail. He even took care to swap personal items into a more secure trouser pocket as he then rode the ship as it went down beneath the waves.

Let me write that again; he rode the ship as it went down beneath the waves. As it sank into the ocean, he simply let go of the rail and floated in the sea, not even getting his hair wet. This act makes Joughin the last person to officially leave the Titanic. Kept afloat by his cork life-vest, he then treaded water for an incredible two hours without dying of hypothermia. The dawn had broken over the horizon by the time he spied what he thought was wreckage. Urging his frozen muscles into action, he swam across and discovered it to be an overturned collapsible lifeboat commanded by Second Officer Lightoller.

Lightoller had been working with a few seamen to get the Titanic’s last collapsible off the submerging deck but had been washed overboard by a wave before they could right it. With nothing left to do but stand on its upturned wooden hull, he helped other people aboard so that a large number of about 25 were all standing up in a packed huddle whilst trying not to either fall off or overturn the sorry excuse for a boat.

It was like this that Joughin came across Lightoller and his ramshackle crew when he swam up to the boat. Attempting to climb aboard and get out of deathly cold water, he was pushed away by someone he didn’t know. Again, having survived for so long against impossible odds only to be denied this one last chance, Joughin could have been forgiven for losing his implacable cool.

Instead, he calmly swam around to the other side and was recognised by the ship’s cook, Maynard. Grasping him by the hand, Maynard kept hold of Joughin, and the chief baker treaded water alongside the upturned boat until another lifeboat came alongside.

The survivors of the collapsible were transferred into this second lifeboat, and Lightoller took command until they were ultimately rescued by the Carpathia. Included in their number was Joughin, and he finally hauled himself out of the freezing sea after floating for an incredible two and half hours. His feet were so badly swollen that he had to climb the rescue ladder on his knees.

The British Inquiry was astounded at his story of survival, and its Chairman quickly came to the conclusion that Joughin had inadvertently saved his own life by drinking strong liquor throughout the sinking, thereby raising his blood alcohol levels and staving off the effects of hypothermia that killed most others who had entered the water.

Joughin survived the disaster and returned home to his wife and two children in Liverpool, England. After his wife’s death in 1919, he eventually settled in the USA and was consulted on the book, A Night To Remember, written by Walter Lord. He died in 1956, two years before the book’s movie adaptation was released to critical acclaim.

His remarkable story is a reminder to us all of the importance of keeping calm in a crisis, and of focusing on what we can do, rather than what we can’t. It’s important to remember we can only influence what is under our direct control, and that we shouldn’t worry too much about things that go beyond that. At the same time, we shouldn’t sit back and allow events to unfold without taking action in some way. Joughin undoubtedly saved lives that night on the 15th April 1912. He may not have saved many lives, and they may not have even been grateful for his efforts, but he played his part and did his duty.

So when life next throws you lemons, make sure you enjoy a glass of lemonade. Or like Joughin, a lemonade vodka on the rocks. Make mine a double.