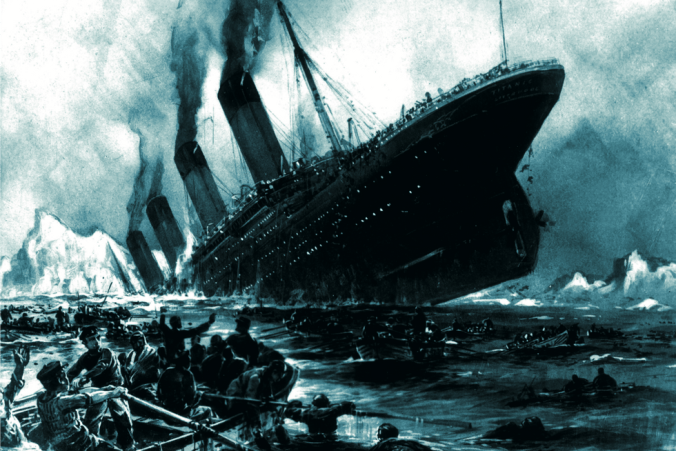

There were enough spaces for 1178 people. But only 706 were saved.

One of the enduring tragedies of the Titanic disaster is the knowledge that so many people perished unnecessarily. Given the fact that this massive ocean liner didn’t carry enough lifeboats to save all crew and passengers in the event of its sinking, we can be forgiven for scratching our heads over the actions of its officers who allowed lifeboats to be lowered less than half full.

How could it have been justified?

Ever since the first news stories were printed following the sinking, a perpetual myth has become ingrained in Titanic’s story. It’s one that cites a lack of organisation in the crew, and of a panic in the ship’s officers who rigidly stuck to their orders of ‘women and children first‘. Stories still abound in the form of books and film that reinforce the image of the Titanic’s officers cruelly (and unnecessarily) hauling terrified men & boys from lifeboats only to lower them half empty to the sound of screamed exhortations from wives & daughters.

Like most stories from history, the truth of why so many lifeboats were lowered at minimal capacity has a simple explanation, and it’s one that is staring us right in the face. All we have to do is go back to the source material. And in this case, from testimonies of the survivors & witnesses themselves…

The Hero: Arthur Rostron, Captain of the Carpathia

The passenger steam ship, Carpathia, was bound for Liverpool from New York when it picked up the distress call from Titanic at 12.35am on 15th April 1912. Its Captain, Arthur Rostron was rudely woken out of bed by his telegraph operator who had barged into his quarters to madly give him the news.

Realising at once the grave situation, and knowing his ship was 58 miles from the Titanic, Rostron gave the order to change course and make for the sinking liner. In a flurry of commands, he had his boilers strained to their maximum output and hurriedly converted his passenger vessel into a hospital ship in anticipation of receiving wounded. Despite his quick thinking and the efforts of his crew, the Carpathia would arrive too late to save anyone from the Titanic directly – the great ship would sink beneath the waves 2 hours before the rescue ship made it to the wreck site. All Rostron and his crew could do was pick up frozen and terrified survivors bobbing around in lifeboats in the middle of the Atlantic.

Deciding to return his now packed ship to New York, Rostron arrived into harbour on the 18th April and was called to a hastily-assembled Senate Inquiry the very next day. Without any time to prepare, the Captain gave a good account of his actions and was lauded by all those present.

It didn’t take long however for the Senate Chairman, Senator William Smith, to ask about the topic of lifeboats;

How many lifeboats did the Carpathia carry? he demanded.

Twenty, came the reply.

What tonnage is the Carpathia?

Rostron was terse in his response; 13,600 tons.

Discussion then pivoted to the Titanic;

How many lifeboats did the Captain believe were held on the Titanic?

Again, the answer of twenty was given

And what tonnage was the Titanic?

45,629 tons

Did Captain Rostron believe there was a problem in this discrepancy since the Carpathia held as many lifeboats as a newer ship that was 3 times as large? Surely a number closer to sixty should have been available on the Titanic?

Rostron’s pragmatic reply gives us an insight into the prevailing attitude of the time;

“The ships are built nowadays to be practically unsinkable, and each ship is supposed to be a

Captain Arthur Rostron

lifeboat in itself. The boats are merely supposed to be put on as a standby. The ships are supposed to

be built, and the naval architects say they are, unsinkable under certain conditions. What the exact

conditions are, I do not know, as to whether it is with alternate compartments full, or what it may be.

That is why in our ship we carry more lifeboats, for the simple reason that we are built differently from

the Titanic; differently constructed.”

His argument is a simple one; because the Titanic was of a modern, safer design, the authorities who drew up the regulations considered it to be a giant lifeboat in itself, capable of staying afloat until another ship on the busy sea lane could arrive to ferry the passengers to safety.

This act of hubris by the British authorities would contribute to the deaths of over 1,500 people in the freezing waters of the Atlantic. It also factored into the thinking by the Titanic’s officers as they helped hundreds of terrified passengers climb into her lifeboats. And this is illustrated perfectly by answers given to the Inquiry by its Second Officer, Charles Lightoller.

The Warrior: Charles Lightoller, Second Officer of the Titanic

Like Rostron, Lightoller was summoned to the Waldorf Astoria where the Senate Inquiry had been assembled the day after the Carpathia had docked. And just like Rostron, he was woefully unprepared for the pointed questioning he’d be placed under.

Aged 38 at the time of the sinking, Lightoller had been the Second Officer of the Titanic, and was pivotal in how the port-side lifeboats had been filled, lowered and sent away from the ship. He had, under his own initiative, organised the evacuation on the port boat deck. He had ordered 2 crew members into each boat for them to take charge once it had been lowered.

The orders given from the Titanic’s captain had been for women and children first, but from Lightoller’s actions, it is clear he interpreted the orders to be women and children only. There are accounts of him dragging men from a lifeboat after they had leapt in just as it was being lowered. He even stated to the Inquiry how he was struggling to find women to put into the final lifeboat, and he casually explains just how many people he allowed in each one.

We take up the questioning at the point where he is asked directly just how many people he placed inside the first lifeboat;

In the first boat I put 20 or 25.

How many men?

No men

How many seamen?

Two

He is then asked what the capacity of the lifeboat was, and he responded;

“Sixty-five in the water.”

Senator Smith then suggests each lifeboat can safely hold forty when being lowered, but Lightoller quickly corrects him by stating only twenty five can be safely loaded. The reason for this was the ship’s davits. A davit is a crane-like apparatus designed for lifting and lowering items from the side of a ship (such as a lifeboat). On the Titanic, they were made of steel and were doubled-up so that each davit supported the forward arm of one boat and the aft arm of the next one along (see photograph below).

But suspending laden boats in this way placed an enormous strain on their keels, and on the davits themselves. The crew of the Titanic, including Lightoller, were aware of this, and as a precaution, they only began the evacuation by placing around 25 people aboard. When questioned, Lightoller explained that he wasn’t aware of the seriousness of their situation when the order was first given to start loading the boats, and so he rigidly stuck to this 25 limit to prevent any sudden collapse and loss of life.

What he didn’t know was that the keel of each lifeboat had been reinforced with steel, and that the White Star Line, who owned the Titanic, had successfully tested the lifeboats on the davits at their maximum capacity of 65. The results of these tests were never passed to the Titanic’s crew, and they were not aware it would have been safe to fully load each boat with 65 people before lowering.

Even at the time of his Senate questioning, Lightoller was blissfully ignorant that his caution in loading the boats had been for nothing. When pressed by Senator Smith, he admits he began loading boats with more and more women as the gravity of their situation became apparent;

Senator SMITH; How many people did you put into it?

LIGHTOLLER: I might have put a good deal more; I filled her up as much as I could. When I got down to the fifth boat, that was aft.

Senator SMITH; You were still using your best judgement?

LIGHTOLLER: I was not using very much judgement then; I was filling them up.

The Senator assumed Lightoller meant he was now filling them to their capacity of 65, but this was wrong. Lightoller himself stated he didn’t knowingly load any of the port-side lifeboats with more than 35 people. For a Second Officer so used to following strict rules and regulations, he was throwing caution to the wind by doing what he saw as overloading his lifeboats. His original intention was for the boats to remain close to the ship once they were safely in the water and collect those passengers remaining onboard. He had portholes opened, and even a gangway door in the hope that terrified passengers would be encouraged to leap into bobbing lifeboats below.

But it was all to no avail. In the pitch black dark with no method to communicate between the Titanic and her lifeboats, there was never any hope of a co-ordinated evacuation. The portholes and gangway door he’d opened only hastened the sinking by providing another access route for incoming seawater. Many of those in the lifeboats were only too keen to row to safety or risk being sucked down with the sinking ship.

Yet it is impossible to blame Lightoller for not loading more people into his lifeboats. It is clear that at some point in the evacuation, Captain Smith of the Titanic had a nervous breakdown, and each officer, whether alone or in pairs, was left to rely on their own initiative. Even the Captain’s famous order of Women and Children First was never properly communicated or explained to Lightoller, who stuck to it without guilt or hesitation. In his mind, until the last woman and child had been safely placed aboard a lifeboat, no man should have been given a space.

The Tragic Conclusion

So why were Titanic’s lifeboats only part-filled? Far from it being due to blind panic from the crew, it was an over-abundance of caution that resulted in so many empty seats going unfilled. It was caution in the underestimated strength of those little wooden boats, and confidence in the overestimated strength of the Titanic. It was this lethal combination of an untested hubris in ocean-liner design, and an over-reliance on dogmatic regulations that ultimately led to unnecessary loss of life. If only The White Star Line had communicated the true strength of the davits and their lifeboats. If only they had conducted live drills as part of the Titanic’s sea trials instead of just testing the gear itself, perhaps many more lives would have been saved.

I’ll end with Lightoller’s response when he was asked if he would have done things differently in hindsight, knowing the true scale of the disaster;

I would have taken more risks. I should not have considered it wise to put more in, but I might have taken risks

Charles Lightoller